Voglio spiegarvi la fobia del grasso

La fobia dei grassi saturi è del tutto ingiustificata ne per nulla supportata dall’evidenza scientifica. Capisco che le persone siano confuse su quali grassi, se i grassi saturi o insaturi fanno male. Cioè quali grassi fanno male. La maggior parte delle persone è ormai convinta (è stata convinta) che i grassi saturi fanno male perchè aumentano il rischio di infarto e ictus.

In questo articolo desidero portarvi LE EVIDENZE sulla ingiustificata fobia dei grassi saturi, raccontandovi prima come ci siamo arrivata, e poi come si procede imperterriti a raccomandare lo stesso abominio con linee guida nutrizionali per quanto concerne i grassi saturi (e non solo questi), campati sulle sabbie mobili.

Purtroppo per decenni ci è stato detto che i grassi saturi sono nocivi, e che per noi vanno meglio gli oli vegetali polinsaturi. Dinanzi a una riduzione dei grassi saturi è nettamente aumentato il consumo di grassi polinsaturi. Questi ultimi però non sono tutti uguali e la costante attenzione sulla quantità di grassi permessi nella dieta dovrebbe essere spostata sulla qualità.

Distinguiamo diverse famiglie di acidi grassi polinsaturi e il loro consumo, eccessivo per alcune categorie e insufficiente per altre, influenza molte funzioni e reazioni chimiche che avvengono nel nostro corpo: come ad esempio il sistema immunitario e la regolazione dell’infiammazione.

Ed è a questa informazione errata che dobbiamo i grandi cambiamenti avvenuti nella nostra alimentazione nel corso degli ultimi decenni. All’inizio del 900 la maggior parte dei grassi assunti erano saturi o monoinsaturi, principalmente provenienti da burro, lardo e olio di oliva. Oggigiorno la maggior parte dei grassi nella dieta sono polinsaturi, prevalentemente di provenienza vegetale come soia, mais, girasole e colza. Abbiamo uno squilibrio nel rapporto omega 3 e omega 6, che ottimalmente dovrebbe essere di 1:1-4, ed invece è di 1:20-40!!! Un tale squilibrio è alla base dell’infiammazione cronica, responsabile delle malattie della nostra epoca. Un rapporto Omega 3 : omega 6 ottimale lo troviamo in popolazioni native, in cui i grassi polinsaturi, monoinsaturi e animali provengono da cibi naturali e non dagli oli raffinati industriai che purtroppo caratterizzano gran parte della nostra alimentazione.

Secondo i LARN (Livelli di Assunzione di Riferimento per la popolazione italiana), la quantità di grassi giornaliera ricopre il 20-35% dell’apporto calorico totale: di questi assolutamente meno del 10% deve provenire da grassi saturi, il resto grassi da grassi monoinsaturi e polinsaturi.

La fobia dei grassi saturi

I grassi di origine animale e vegetale forniscono sia un notevole apporto energetico alla nostra dieta, sia materiale per la formazione di membrane cellulari, ormoni e sostanze ormono-simili. Se fanno parte di un pasto riducono la velocità di assorbimento di altri alimenti, diminuendo il nostro senso di fame. Essi garantiscono l’assorbimento delle importanti vitamine liposolubili A, D, E e K.

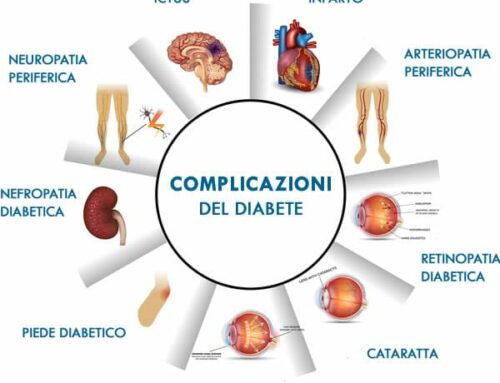

Le indicazioni dietetiche dettate dalle cosiddette linee guida ufficiali si basano sulla teoria che dobbiamo ridurre l’introito di grassi, specie quelli saturi di origine animale. Mai come negli ultimi trent’anni abbiamo ridotto a livello mondiale il consumo di grassi saturi, e mai, come adesso, siamo stati così malati; basti pensare ai numeri vertiginosi di obesità, infarto, ictus, diabete, ipertensione arteriosa, demenza, Alzheimer, cancro, osteoporosi, carie, gastrite.

Abbiamo sostituito il consumo di grassi sani con un consumo abnorme di carboidrati raffinati associati a olii vegetali polinsaturi in ogni forma: pasta, cracker, grissini, biscotti, torte, pizze, brioches, merendine, ecc.

Quando è iniziata la fobia dei grassi saturi?

“Dopo 40 anni abbiamo visto che più grassi saturi e colesterolo e quindi più elevate erano le calorie consumate, meno elevati risultavano i livelli di colesterolo nel sangue di questo gruppo, che pesava di meno ed era fisicamente più attivo. Ciò significa che l’aumento di peso e di colesterolo non ha un rapporto direttamente proporzionale con l’introito di grassi saturi con l’alimentazione”.

William Castelli, cardiologo e direttore del Framingham Heart Study, uno studio molto noto nell’ambiente medico, iniziato nel 1948 nella cittadina statunitense di Framingham, nel Massachusetts, che ha coinvolto 6000 persone del luogo, suddividendole in 2 gruppi, analizzati ad intervalli di 5 anni, il primo gruppo con consumo minimo di colesterolo e grassi saturi e il secondo gruppo con largo consumo dei medesimi grassi

Il tutto inizio nel 1913 quando Nikolai Anitschkow, un patologo russo, fece un esperimento sui conigli nutrendoli con colesterolo puro, e facendo salire i loro livelli di colesterolo nel sangue a 1000 mg/dl. Rilevò quindi la formazione di lesioni arteriose sovrapponibili con la nostra aterosclerosi. La connessione fu subito fatta: per abbassare il colesterolo nel sangue bisognava mangiarne di meno: niente di più sbagliato.

Ricordiamoci, però, che i conigli sono animali puramente erbivori, non biologicamente predisposti a metabolizzare cibo di origine animale. È curioso che nello steso periodo venne fatto uno studio simile, su cani e ratti, notoriamente onnivori, in cui la somministrazione di colesterolo non provocò assolutamente alcuna lesione.

Ma, probabilmente, il vero responsabile della ormai corrente e diffusa convinzione che l’infarto è la conseguenza del consumo di grassi saturi che portano ad un aumento della colesterolemia risale agli anni 70 per opera di Ancel Keys, un fisiologo americano, che con il suo studio “Seven Country Study” voleva palesare lo stretto legame tra quantità di grassi consumati e rischio di infarto in 7 paesi.

È proprio a questo studio che si rifanno le linee guida alimentari e su di esso si basa la famigerata piramide alimentare, purtroppo ancora oggi.

Numerosi ricercatori, negli anni a venire, hanno additato gli errori di questa teoria, ma purtroppo, Keys ricevette un’enorme attenzione dai media, manovrati dall’industria agroalimentare con interessi miliardari, la principale beneficiaria di questa visione. La stessa industria alimentare che produce ancora oggi oli vegetali e cibi industrialmente raffinati, con profitti enormi, in grado quindi di finanziare nuovi studi pilotati al fine di corroborare la lipid hypothesis, tutto a nostre spese.

Il fatto tragico è che originariamente Ancel Keys valutò 22 paesi differenti, ma nella sua pubblicazione ne inserì solo 7; dove sono finiti gli altri 15?? Non sono stati considerati perché i dati non confermavano l’ipotesi dello scienziato: infatti gli alti valori di colesterolo non correlavano con un infarto o meglio, ad un infarto non corrispondevano elevati valori di colesterolemia.

A ciò si aggiunge un’altro grave difetto dello studio di Ancel Keys: era di naturale epidemiologica, ovvero, se anche fosse stato esatto, non è comunque sufficiente per rappresentare una relazione causale colesterolo elevato e infarto.

Negli ultimi anni sono molti gli studi eseguiti che analizzano l’eventuale rapporto tra grassi saturi e malattie cardiache: non è mai stato riscontrato alcun nesso tra loro!! Fra tutti gli studi ve ne cito solo uno del 2012 della Cochrane Database*: trattasi di una metanalisi di 48 studi, in cui veniva esaminato l’effetto della riduzione di grasso o la modifica dei grassi nella dieta.

I partecipanti riducevano l’introito di grassi saturi e/o li sostituivano con grassi polinsaturi, cioè oli vegetali. Il risultato è stato che l’intervento dietetico non ha ridotto né il rischio di morte per malattie cardiovascolari né quello di morte in generale. Perché non ne avete mai sentito parlare? Perché nessuno aveva l’interesse a rendere noto questo studio, ma piuttosto a tenerlo occulto.

Qualora qualcuno volesse addentrarsi in materia, posso solo consigliare la letture di tre testi, che per me sono stati particolarmente illuminanti, a dir poco:

· Know your fats, (Conosci i tuoi grassi), di Mary Enig, insigne biochimica nutrizionista, che nel suo testo disserta sul tema grassi con dovizia e precisione, come pochi.

· Fat and cholesterol are good for you, (Il grasso e il colesterolo ti fanno bene) di Uffe Ravnskov, medico svedese, che come nessun altro disquisisce sul tema grassi.

· The big fat surprise, (La grande sorpresa grassa) di Tina Teihholz, giornalista scientifica, che con il suo volume ha indagato minuziosamente il tema.

Ne conseguono decenni di indicazioni errate sull’alimentazione, che hanno arrecato danni incalcolabili alla nostra salute. Il maggiore profitto lo ha derivato l’industria alimentare, che sull’onda isterica della fobia legata ai grassi saturi ha commercializzato un’infinità di prodotti con oli vegetali di bassa qualità, acidi grassi trans e cibi light!!

*GL Hooper et al: Reduced or modified dietary fat for preventing cardiovascular disease, in „Cochrane Database Syst Rev“, 16. Mai; (5): CD 0021

Sono numerosi gli studi su popolazioni tradizionali che rappresentano un imbarazzo per gli autocrati della dieta:

· I Masai, fondamentalmente gli uomini, si nutrono prevalentemente di latte, sangue e carne: hanno livelli bassi di colesterolemia e non hanno malattie cardiache.

· Gli Eschimesi si cibavano esclusivamente di grasso animale di pesci di mare: seguendo la loro dieta nativa queste popolazioni non hanno mai avuto le malattie tipiche della civiltà industrializzata che ci caratterizza. Venuti a contatto però con le abitudini alimentari occidentali anch’essi hanno cominciato a sviluppare le medesime patologie.

· In Cina le regioni ad alto consumo di latte intero e prodotti derivati presentava la metà di casi di malattie cardiache rispetto ad aree con un minor consumo di grassi animali.

· Numerose popolazioni mediterranee presentano una bassa incidenza di cardiopatie nonostante il grasso consumato arrivi al 70% – incluso quello saturo proveniente da agnello, latticini di origine caprina. Gli abitanti di Creta erano famosi per la loro buona salute e longevità.

· A Okinawa, in Giappone, dove l’età media delle donne è di 84 anni, gli abitanti mangiano grandi quantità di carne di maiale e pesce, cucinando il tutto nel lardo.

· La relativa buona salute dei Giapponesi, che sono tra i più longevi al mondo, viene erroneamente attribuita ad un’alimentazione povera di grassi. In verità essi mangiano moderate quantità di grassi animali provenienti dalle uova, maiale, pollo, manzo, pesci di mare e carni biologiche. Con le quantità di crostacei e brodo di pesce consumate dai giapponesi, è probabile che assumano più colesterolo di noi.

Cosa sicuramente non consumano sono grandi quantità di oli vegetali, farina bianca o cibi raffinati (anche se mangiano riso). La loro vita media è aumentata dalla seconda guerra mondiale insieme al consumo di grassi animali e proteine nella loro dieta.

· Gli svizzeri hanno una longevità pari a quella dei giapponesi, nonostante un’alimentazione tra le più grasse al mondo.

· In Francia l’alimentazione è ricca di grassi saturi provenienti da burro, uova, formaggi, crema, fegato, carne e paté. I francesi però presentano meno cardiopatie coronariche rispetto alle altre popolazioni occidentali. Pensate che nella regione della Guascogna, dove il fegato di anatra e oca è un caposaldo della loro dieta, hanno un’incidenza di coronaropatia di 80 per 100.000 abitanti. Questo fenomeno è noto come il french paradox (paradosso francese). Ad onor del vero dobbiamo però anche dire che i francesi soffrono di molte malattie degenerative, ascrivibile al largo consumo di zuccheri e cereali raffinati.

Eccovi ora dei tratti dell’articolo di Nina Teichholz, giornalista scientifica e investigativa americana, autrice del libro The big fat surprise:

A short history of saturated fat: the making and unmaking of a scientific consensus

La fobia dei grassi saturi – risultati recenti

Le recenti scoperte includono carenze nei processi di revisione scientifica sui grassi saturi, sia per le attuali Linee guida dietetiche per gli americani 2020-2025 che per l’edizione precedente (2015-2020).

Le rivelazioni includono il fatto che il Comitato consultivo del 2015 ha riconosciuto, in un’e-mail, la mancanza di giustificazione scientifica per qualsiasi limite numerico specifico su questi grassi. Altre scoperte, non pubblicate in precedenza, includono significativi potenziali conflitti finanziari nel sottocomitato delle linee guida 2020, tra cui la partecipazione di sostenitori di una dieta a base vegetale, di un esperto che promuove una dieta a base vegetale per motivi religiosi, di esperti che hanno ricevuto ampi finanziamenti da industrie, come quelle della frutta a guscio e della soia, i cui prodotti traggono vantaggio dal mantenimento di raccomandazioni politiche a favore dei grassi polinsaturi, e di un’esperta che ha dedicato più di 50 anni della sua carriera a “dimostrare” l’ipotesi della dieta per il cuore.

STUDI SUI GRASSI SATURI

I governi di tutto il mondo, tra cui gli Stati Uniti, la Norvegia, la Finlandia e l’Australia, hanno riconosciuto la necessità di disporre di dati clinici più rigorosi che potessero stabilire una relazione causale tra i grassi saturi e le malattie cardiache.

Negli anni ’60 e ’70 sono stati condotti grandi studi clinici randomizzati e controllati (RCT) in cui i grassi saturi sono stati sostituiti da grassi polinsaturi provenienti da oli vegetali.

Complessivamente, questi studi “centrali” hanno testato l’ipotesi dieta-cuore su circa 67.000 persone [15] e sono stati particolarmente importanti perché hanno valutato gli esiti clinici a lungo termine, cioè gli “endpoint difficili”, come l’infarto e la morte. Questi risultati sono considerati più affidabili per la definizione di politiche di salute pubblica rispetto agli studi che utilizzano “endpoint intermedi”, come il colesterolo o le misure infiammatorie, il cui valore per la previsione di eventi cardiovascolari è discusso.

Questi studi hanno fornito un sostegno sorprendentemente scarso all’ipotesi dieta-cuore. Secondo un’analisi, le drastiche riduzioni del consumo di grassi saturi hanno abbassato con successo il colesterolo dei partecipanti, in media di 29 mg/dl, “indicando un alto livello di compliance” tra i soggetti [16], ma nella maggior parte degli studi non sono state osservate le previste riduzioni della mortalità cardiovascolare o totale [15]. In altre parole, sebbene la dieta potesse ridurre con successo il colesterolo nel sangue, questa riduzione non sembrava tradursi in vantaggi cardiovascolari a lungo termine.

Quando questi risultati emersero, tuttavia, l’ipotesi di Keys aveva già ottenuto un’ampia accettazione da parte dei suoi colleghi, compresa, cosa importante, la leadership del National Institutes of Health (NIH) [2]. Alla fine degli anni ’60, il pregiudizio a favore dell’ipotesi dieta-cuore era abbastanza forte che i ricercatori con risultati contrari si trovarono nell’impossibilità o nella non volontà di pubblicare i loro risultati.

Ad esempio, il più grande studio dell’ipotesi dieta-cuore, il Minnesota Coronary Survey, che ha coinvolto 9057 uomini e donne per 4,5 anni, ha testato una dieta con il 18% di grassi saturi rispetto a controlli che ne consumavano il 9%, ma non ha riscontrato alcuna riduzione degli eventi cardiovascolari, dei decessi per cause cardiovascolari o della mortalità totale [17].

Sebbene lo studio fosse stato finanziato dal NIH, i risultati non furono pubblicati per 16 anni. La decisione di Ivan Frantz, il ricercatore principale, di non pubblicare tempestivamente i risultati ha fatto sì che questi dati contraddittori non venissero presi in considerazione per altri 40 anni [18].

Altri risultati non pubblicati provengono da una delle più famose indagini sulle malattie cardiache mai intraprese, il Framingham Heart Study, iniziato nel 1948. Il professore della Vanderbilt University George Mann condusse un’indagine sulla dieta, raccogliendo dati dettagliati sul consumo di cibo da 1049 soggetti [19]. Quando nel 1960 calcolò i risultati, fu molto chiaro che i grassi saturi non erano correlati alle malattie cardiache.

Per quanto riguarda l’incidenza della malattia coronarica e la dieta, gli autori conclusero semplicemente: “Non è stata trovata alcuna relazione” [20]. Tuttavia, solo nel 1992 un responsabile dello studio Framingham ha riconosciuto pubblicamente i risultati dello studio sui grassi.

A Framingham, in Massachusetts, più grassi saturi si mangiavano. … più basso era il colesterolo sierico della persona… e [questi] pesavano meno”, scrisse William P. Castelli, uno dei direttori del Framingham, in un commento informale [21].

Come conseguenza della mancata pubblicazione o dell’ignoranza dei risultati degli studi contrari all’ipotesi dieta-cuore, per decenni la maggior parte degli esperti di nutrizione non ha preso in seria considerazione l’idea che i grassi saturi fossero stati ingiustamente diffamati.

RICONSIDERAZIONE DEGLI STUDI SUI GRASSI SATURI

Negli anni ’60 e ’70 non erano sconosciute le recensioni e i libri critici nei confronti dell’ipotesi dieta-cuore, tra cui una pubblicazione di un ex redattore del Journal of the American Heart Association [22] e articoli di altri importanti scienziati [23-25]. Essi sostenevano che l’ipotesi non era supportata dai dati disponibili ed era contraddetta da numerose osservazioni.

Nel corso del tempo, tuttavia, questi critici sono stati effettivamente emarginati e messi a tacere [2]. Solo negli anni 2000 questa scienza è tornata alla luce, soprattutto grazie al lavoro del giornalista Gary Taubes [26,27]. La prima raccolta completa di argomenti sul perché i grassi saturi non fanno male alla salute è stata pubblicata da questo autore, anch’egli giornalista [2].

Le prime analisi formali dei primi dati sui grassi saturi sono state condotte da Ronald M. Krauss, cardiologo ed esperto di nutrizione, e pubblicate in due articoli sull’American Journal of Clinical Nutrition nel 2010 [28,29]. Krauss ha incontrato ostacoli incredibili nel processo di revisione paritaria, evidentemente a causa della resistenza diffusa a rivalutare un’ipotesi di lunga data [2]. Un collega di Keys ha tentato di confutare questi documenti [30], ma poco dopo altri scienziati si sono uniti a Krauss per rivalutare gli stessi dati.

I risultati degli studi di Keys sono stati ampiamente rivisti da scienziati di tutto il mondo, compreso il prestigioso Gruppo Cochrane, da ultimo nel 2020. Complessivamente, sono stati pubblicati più di 20 articoli di revisione, comprese le rassegne cosiddette ad ombrello (umbrella reviews), la maggior parte dei quali conclude che i dati degli studi randomizzati controllati non forniscono prove coerenti o adeguate per continuare a raccomandare la limitazione dell’assunzione di grassi saturi [15].

Alcune revisioni hanno dato risultati contrari [31,32], ma questi sono stati principalmente spiegati dall’inclusione di uno studio, chiamato Finnish Mental Hospital Study, che non aveva un’adeguata randomizzazione, tra gli altri problemi, ed è stato quindi escluso nelle revisioni più recenti [16]. Il risultato della Cochrane 2020 di un effetto sugli eventi cardiovascolari è scomparso quando è stato sottoposto a un’analisi di sensibilità all’interno del rapporto, in cui sono stati esclusi gli studi che non avevano ridotto con successo i grassi saturi [33▪▪].

Le revisioni che si sono concentrate sul colesterolo LDL hanno ignorato gli esiti a lungo termine, molto più definitivi, degli eventi cardiovascolari e della mortalità [31,32]. Nel complesso, quindi, nonostante l’ampia sperimentazione dell’ipotesi dieta-cuore, i dati non supportano il continuo consiglio di limitare questi grassi per la prevenzione delle malattie cardiache.

I risultati di studi osservazionali o epidemiologici costituiscono dati meno solidi, poiché questi studi si limitano solitamente a dimostrare associazioni piuttosto che relazioni di causa-effetto.

Tuttavia, i risultati epidemiologici sostanziali che contraddicono un’ipotesi forniscono una ragionevole evidenza che l’ipotesi potrebbe essere errata. I dati del più grande studio epidemiologico di coorte mai condotto, chiamato Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE), forniscono questo tipo di prova contraddittoria riguardo all’ipotesi dieta-cuore. PURE ha seguito persone di età compresa tra i 35 e i 70 anni dal 2003 al 2013 in 18 Paesi, con un follow-up mediano di 7,4 anni.

Tuttavia, i risultati epidemiologici sostanziali che contraddicono un’ipotesi forniscono una ragionevole evidenza che l’ipotesi potrebbe essere errata. I dati del più grande studio epidemiologico di coorte mai condotto, chiamato Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE), forniscono questo tipo di prova contraddittoria riguardo all’ipotesi dieta-cuore. PURE ha seguito persone di età compresa tra i 35 e i 70 anni dal 2003 al 2013 in 18 Paesi, con un follow-up mediano di 7,4 anni.

I ricercatori di PURE hanno scoperto che i grassi saturi non erano associati al rischio di infarto del miocardio o di mortalità per malattie cardiovascolari, mentre erano significativamente associati a una minore mortalità totale e al rischio di ictus [34].

Quest’ultimo risultato, relativo all’ictus, è particolarmente significativo perché è coerente con altri studi osservazionali [35], e i grassi saturi sono l’unico tipo di grasso che risulta avere un effetto positivo su questo importante risultato per la salute cerebrovascolare. Inoltre, nove revisioni di dati osservazionali condotte a partire dal 2010 non hanno rilevato associazioni significative tra il consumo di questi grassi e le malattie coronariche [15].

Quest’ultimo risultato, relativo all’ictus, è particolarmente significativo perché è coerente con altri studi osservazionali [35], e i grassi saturi sono l’unico tipo di grasso che risulta avere un effetto positivo su questo importante risultato per la salute cerebrovascolare. Inoltre, nove revisioni di dati osservazionali condotte a partire dal 2010 non hanno rilevato associazioni significative tra il consumo di questi grassi e le malattie coronariche [15].

Dati epidemiologici di questa qualità e portata contribuiscono in modo significativo alla comprensione del rapporto tra grassi saturi e malattie cardiovascolari. Questi dati rafforzano i risultati degli studi clinici più rigorosi descritti in precedenza.

Nonostante queste ampie scoperte che sfatano la relazione tra grassi saturi e malattie cardiache, le speculazioni sull’ipotesi dieta-cuore continuano. Ad esempio, la rivista Circulation dell’AHA ha pubblicato i risultati di un’associazione tra l’acido grasso linoleico, uno dei principali componenti degli oli vegetali, e una minore incidenza di eventi cardiovascolari e mortalità [36]. Tuttavia, questa scoperta si basa su dati non standardizzati, a livello di Paese (ecologici), che sono generalmente considerati tra le prove di qualità più bassa.

LINEE GUIDA DIETETICHE STATUNITENSI SUI GRASSI SATURI

Il governo statunitense è stato il primo al mondo a raccomandare una restrizione dei grassi saturi.

Nel 1977 ilComitato ristretto del Senato degli Stati Uniti sulla nutrizione e i bisogni umani pubblicò gli Obiettivi dietetici per gli Stati Uniti, in cui si raccomandava al pubblico di “ridurre il consumo di grassi saturi in modo che rappresentassero circa il 10% dell’apporto energetico totale” [37]. Il rapporto è stato fortemente influenzato dagli esperti dell’AHA ed è stato scritto da un singolo membro del Senato senza alcuna preparazione in campo scientifico o nutrizionale [26].

Una prima bozza del rapporto raccomandava inoltre di “ridurre il consumo di carne”, in base al suo contenuto di grassi saturi. Questo consiglio è stato rivisto con la dicitura: “scegliete carni… che riducano l’assunzione di grassi saturi”, ponendo l’accento sulla “carne magra”. Alcuni osservatori hanno interpretato questa revisione come dovuta esclusivamente all’interferenza dell’industria della carne, ma un articolo del 2014 dell’American Journal of Public Health, che ha esaminato in dettaglio il processo della commissione del Senato, conclude che “la mancanza di consenso scientifico” è stata la ragione principale della modifica del linguaggio sulla carne [38]. Quest’ultima interpretazione riflette anche l’assenza di dati rigorosi che colleghino i grassi saturi alle malattie cardiache, come descritto in precedenza.

Gli obiettivi dietetici hanno portato all’istituzione di una politica, emessa congiuntamente dai Dipartimenti dell’Agricoltura e della Salute e Servizi Umani degli Stati Uniti (USDA-HHS), denominata Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA), pubblicata per la prima volta nel 1980 e da allora ogni 5 anni [39]. L’edizione inaugurale delle linee guida includeva il consiglio di “evitare troppi grassi, grassi saturi e colesterolo”, ma non prevedeva un limite numerico specifico per i grassi saturi. Le linee guida del 1990 e tutte le edizioni successive hanno incluso l’obiettivo di limitare questi grassi al 10% delle calorie totali o meno.

Secondo la legge statunitense, le DGA devono riflettere “la preponderanza delle conoscenze scientifiche e mediche attuali al momento della preparazione del rapporto” [40]. L’argomento dei grassi saturi presenta tuttavia una difficoltà unica, poiché gli studi di base originali si sono conclusi prima dell’inizio delle linee guida. Una revisione di tutti i rapporti degli esperti della DGA ha rilevato che nessuno dei comitati di esperti incaricati di rivedere la scienza per ogni nuova edizione delle linee guida aveva mai intrapreso una revisione diretta e sistematica di questi studi di base sui grassi saturi [41].

Le linee guida avevano semplicemente ereditato l’opinione ampiamente diffusa che i grassi saturi fossero legati alle malattie cardiovascolari senza una propria revisione scientifica.

Una crescente consapevolezza degli studi di base a partire dal 2010 avrebbe dovuto spingere uno dei successivi Comitati consultivi per le linee guida dietetiche (DGAC) ad avviare una revisione sistematica di questi studi principali, ma non è stato fatto. Il DGAC del 2015 ha deciso, in una fase avanzata del processo delle DGA, di intraprendere una nuova revisione dei grassi saturi, in risposta alla pubblicazione di un documento di revisione su questo argomento, con autori tra cui professori delle Università di Cambridge e Harvard [42], e di un importante articolo del Wall Street Journal sullo stesso argomento [43].

Entrambe le pubblicazioni suggerivano la mancanza di prove che collegassero i grassi saturi alle malattie cardiache. La decisione del DGAC di avviare una revisione dei grassi saturi è stata rivelata da alcune e-mail ottenute grazie a una richiesta presentata ai sensi della legge sulla libertà di informazione e riflette il disagio di alcuni membri del DGAC per il fatto che queste pubblicazioni “contraddicono le conclusioni dell’AHA” sui grassi saturi [44].

La vicepresidente della DGAC, Alice Lichtenstein, una scienziata della Tufts University che ha anche presieduto per due volte il comitato nutrizionale dell’AHA, ha suggerito in un’e-mail agli altri membri della DGAC di fissare un limite numerico per i grassi saturi, anche se, ha scritto, “non c’è alcuna magia/dato per il numero del 10% o del 7% che è stato usato in precedenza” [45].

L’analisi della DGAC del 2015 sui grassi saturi, risultante da questo scambio di e-mail, è stata una revisione narrativa e non sistematica di sette documenti di revisione esterni [46]. Due analisi di questa revisione della DGAC del 2015 hanno rilevato che essa ha omesso almeno un documento con risultati nulli sui grassi saturi, mentre ha incluso in modo inappropriato altri documenti che sostenevano il consiglio di promuovere gli oli vegetali rispetto ai grassi saturi [11,33].

In un caso, il DGAC ha incluso un documento che riguardava esclusivamente l’acido linoleico e non i grassi saturi [47]. In un altro caso, è stato incluso un lavoro di revisione che si basava in larga misura sullo studio dell’ospedale psichiatrico finlandese, i cui dati, per ragioni già discusse, erano stati ritenuti inaffidabili [16]. Il risultato è stato evidentemente una revisione della DGAC che non ha fornito una valutazione equilibrata o approfondita dei documenti di revisione esterni in vigore al momento della stesura del rapporto del 2015.

La DGAC del 2015 ha concluso che le prove di una relazione tra grassi saturi e malattie cardiache sono “forti”.

Per le linee guida del 2020, il DGAC ha condotto anche una revisione dei grassi saturi [48]. Una recente analisi degli studi inclusi in questa revisione ha rilevato che l’88% non supporta un legame tra questi grassi e le malattie cardiache [33].

La fobia dei grassi saturi – CONCLUSIONI

Per decenni dopo l’introduzione dell’ipotesi dieta-cuore, molti scienziati non erano consapevoli della mancanza di prove a sostegno di questa teoria. Tuttavia, la riscoperta di rigorosi studi clinici che hanno testato questa ipotesi e la successiva pubblicazione di numerosi articoli di revisione su questi dati hanno fornito una nuova consapevolezza della fondamentale inadeguatezza delle prove a sostegno dell’idea che i grassi saturi causino malattie cardiache.

La resistenza osservata contro la considerazione di questa nuova scienza da parte delle successive DGAC può essere vista come il riflesso di pregiudizi di lunga data nel campo e dell’influenza di interessi acquisiti. Finché la recente scienza sui grassi saturi non sarà incorporata nelle linee guida dietetiche degli Stati Uniti, (ma anche da noi in ITALIA), la politica su questo argomento non potrà essere considerata basata sulle evidenze.

Bibliografia

1. Taubes G. Good calories, bad calories. New York: Alfred A. Knopf; 2007. [Google Scholar]

2. Teicholz N. The big fat surprise. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 2014. [Google Scholar]

3. Keys A, Anderson JT, Fidanza F, et al.. Effects of diet on blood lipids in man. Clin Chem 1955; 1:34–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Keys A. Studies on serum cholesterol and other characteristics of clinically healthy men in Naples. Arch Intern Med 1954; 93:328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Keys A, Vivanco F, Minon JLR, et al.. Studies on the diet, body fatness and serum cholesterol in Madrid, Spain. Metabolism 1954; 3:195–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Page IH, Allen EV, Chamberlain FL, et al.. Dietary fat and its relation to heart attacks and strokes. Circulation 1961; 23:133–136. [Google Scholar]

7. Marvin HM. 1924–1964: the 40 year war on heart disease. New York: American Heart Association; 1964. [Google Scholar]

8. Bentley J. U.S. trends in food availability and a dietary assessment of loss-adjusted food availability, 1970–2014. Usda.gov. 2017. Available at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/82220/eib-166.pdf?v=42762 [cited 2022 Jul 21]. [Google Scholar]

9. Keys A. Coronary heart disease in seven countries. Circulation 1970; 3:1–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Blackburn H, Jacobs D, Jr, Kromhout D, Menotti A. Review of Big Fat Surprise should have questioned author’s claims. Lancet 2018; 392:1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Teicholz N. Response to critique of review of The Big Fat Surprise. Lancet 2019; 393:2124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Leland GA. Crete: a case study of an underdeveloped area. 1953; Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, p. 103. [Google Scholar]

13. Sarri K, Kafatos A. The seven countries study in Crete: Olive oil, Mediterranean diet or fasting? Public Health Nutr 2005; 8:666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Menotti A, Kromhout D, Blackburn H, et al.. Food intake patterns and 25-year mortality from coronary heart disease: cross-cultural correlations in the Seven Countries Study. Eur J Epidemiol 1999; 15:507–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Astrup A, Magkos F, Bier DM, et al.. Saturated fats and health: a reassessment and proposal for food-based recommendations. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020; 76:844–857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Hamley S. The effect of replacing saturated fat with mostly n-6 polyunsaturated fat on coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Nutr J 2017; 16:30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Frantz ID, Jr, Dawson EA, Ashman PL, et al.. Test of effect of lipid lowering by diet on cardiovascular risk. The Minnesota Coronary Survey. Arteriosclerosis 1989; 9:129–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Ramsden CE, Zamora D, Majchrzak-Hong S, et al.. Re-evaluation of the traditional diet-heart hypothesis: analysis of recovered data from Minnesota Coronary Experiment (1968–73). BMJ 2016; 353:i1246. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Mann GV, Pearson G, Gordon T, Dawber TR. Diet and cardiovascular disease in the Framingham study. I. Measurement of dietary intake. Am J Clin Nutr 1962; 11:200–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Kannel WB, Gordon T. The Framingham Study: an epidemiological investigation of cardiovascular disease. Unpublished paper. Washington, DC: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute: 1987; 24. Available at: https://www.scribd.com/document/583903774/Kannel-W-Gordon-T-Framingham-dietary-data-Section-24-unpublished. [Google Scholar]

21. Castelli WP. Concerning the possibility of a nut. Arch Intern Med 1992; 152:1371–1372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Pinckney ER, Pinckney C. The cholesterol controversy. Los Angeles: Sherbourne Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

23. Mann GV. Discarding the diet-heart hypothesis. Nature 1978; 271:500. [Google Scholar]

24. Ahrens EH, Jr. Introduction. Am J Clin Nutr 1979; 32:2627–2631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Reiser R. Saturated fat in the diet and serum cholesterol concentration: a critical examination of the literature. Am J Clin Nutr 1973; 26:524–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Taubes G. Nutrition. The soft science of dietary fat. Science 2001; 291:2536–2545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Taubes G. What if it’s all been a big fat lie? The New York Times. 2002 Jul 7; Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2002/07/07/magazine/what-if-it-s-all-been-a-big-fat-lie.html. [Google Scholar]

28. Siri-Tarino PW, Sun Q, Hu FB, Krauss RM. Saturated fat, carbohydrate, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr 2010; 91:502–509. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Siri-Tarino PW, Sun Q, Hu FB, Krauss RM. Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating the association of saturated fat with cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr 2010; 91:535–546. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Stamler J. Diet-heart: a problematic revisit. Am J Clin Nutr 2010; 91:497–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Mozaffarian D, Micha R, Wallace S. Effects on coronary heart disease of increasing polyunsaturated fat in place of saturated fat: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS Med 2010; 7:3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Sacks FM, Lichtenstein AH, Wu JHY, et al.. Dietary fats and cardiovascular disease: a presidential advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017; 136:e1–e23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33▪▪. Astrup A, Teicholz N, Magkos F, et al.. Dietary saturated fats and health: are the U.S. guidelines evidence-based? Nutrients 2021; 13:3305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]This paper contains an original, detailed analysis of the saturated fats review by the 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee and concludes that 88% of the studies reviewed did not support the committee’s conclusion.

34. Dehghan M, Mente A, Zhang X, et al.. Associations of fats and carbohydrate intake with cardiovascular disease and mortality in 18 countries from five continents (PURE): a prospective cohort study. Lancet 2017; 390:2050–2062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Kang Z-Q, Yang Y, Xiao B. Dietary saturated fat intake and risk of stroke: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2020; 30:179–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Marklund M, Wu JHY, Imamura F, et al.. Biomarkers of dietary omega-6 fatty acids and incident cardiovascular disease and mortality: An individual-level pooled analysis of 30 cohort studies. Circulation 2019; 139:2422–2436. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs; U.S. Senate. Ninety-Fifth Congress Session 1, Dietary Goals for the United States; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1977. Available at: https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/011389409. [Google Scholar]

38. Oppenheimer GM, Benrubi ID. McGovern’s Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs versus the meat industry on the diet-heart question (1976–1977). Am J Public Health 2014; 104:59–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. U.S. Department of Agriculture; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary guidelines for Americans. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 1980–2020. Available at: https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/about-dietary-guidelines/previous-editions. [Google Scholar]

40. U.S. Congress. National Nutrition Monitoring and Related Research Act of 1990. U.S. Congress. Washington, DC, USA; 1990. [Google Scholar]

41. Teicholz N. The scientific report guiding the US dietary guidelines: is it scientific? BMJ 2015; 351:h4962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Chowdhury R, Warnakula S, Kunutsor S, et al.. Association of dietary, circulating, and supplement fatty acids with coronary risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160:398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Teicholz N. The questionable link between saturated fat and heart disease. Wall Street Journal. 2014 May 2. Available at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-questionable-link-between-saturated-fat-and-heart-disease-1399070926 [cited 2022 Jul 26]. [Google Scholar]

44. Records obtained via a Freedom of Information Act request. Available at: https://www.scribd.com/document/311738813/Part-1-of-2-response-to-my-11-18-15-FOIA-request-re-2015-US-DGAC-members-Barbara-Millen-Alice-Lichtenstein-Frank-Hu, 30–38. [Accessed July 25, 2022]. [Google Scholar]

45. Records obtained via a Freedom of Information Act request. Available at: https://www.scribd.com/document/312807180/Part-2-of-2-response-to-my-11-18-15-FOIA-request-re-2015-US-DGAC-members-Barbara-Millen-Alice-Lichtenstein-Frank-Hu, 363–364. [Google Scholar]

46. Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee; U.S. Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2015. Washington, DC, USA: Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service; 2015. [Google Scholar]

47. Farvid MS, Ding M, Pan A, et al.. Dietary linoleic acid and risk of coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Circulation 2014; 130:1568–1578. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee; U.S. Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020. Washington, DC, USA: Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service; 2020. [Google Scholar]

49. Demasi M. US nutritionists call for dietary guideline limits on saturated fat intake to be lifted. BMJ 2020; 371:m4226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Fuster V. Editor-in-chief’s top picks from 2021. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022; 79:695–753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Nutrition Coalition. Unbalanced, One-sided Subcommittee on Saturated Fats. April 7, 2020. Available at: https://www.nutritioncoalition.us/news/unbalanced-subcommittee-on-saturated-fat [Accessed July 14, 2022]. [Google Scholar]

52▪▪. Mialon M, Serodio P, Crosbie E, et al.. Conflicts of interest for members of the U.S. 2020 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Public Health Nutr 2022. 1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]This is the first-ever systematic analysis of financial conflicts of interest on any U.S. Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, and it reveals that 95% of the 2020 committee had at least one tie to the food or pharmaceutical industries.

53. The truth about saturated fat. True Health Initiative. 2019. Available at: https://www.truehealthinitiative.org/making_the_news/the-truth-about-saturated-fat/ [cited 2022 Jul 28]. [Google Scholar]